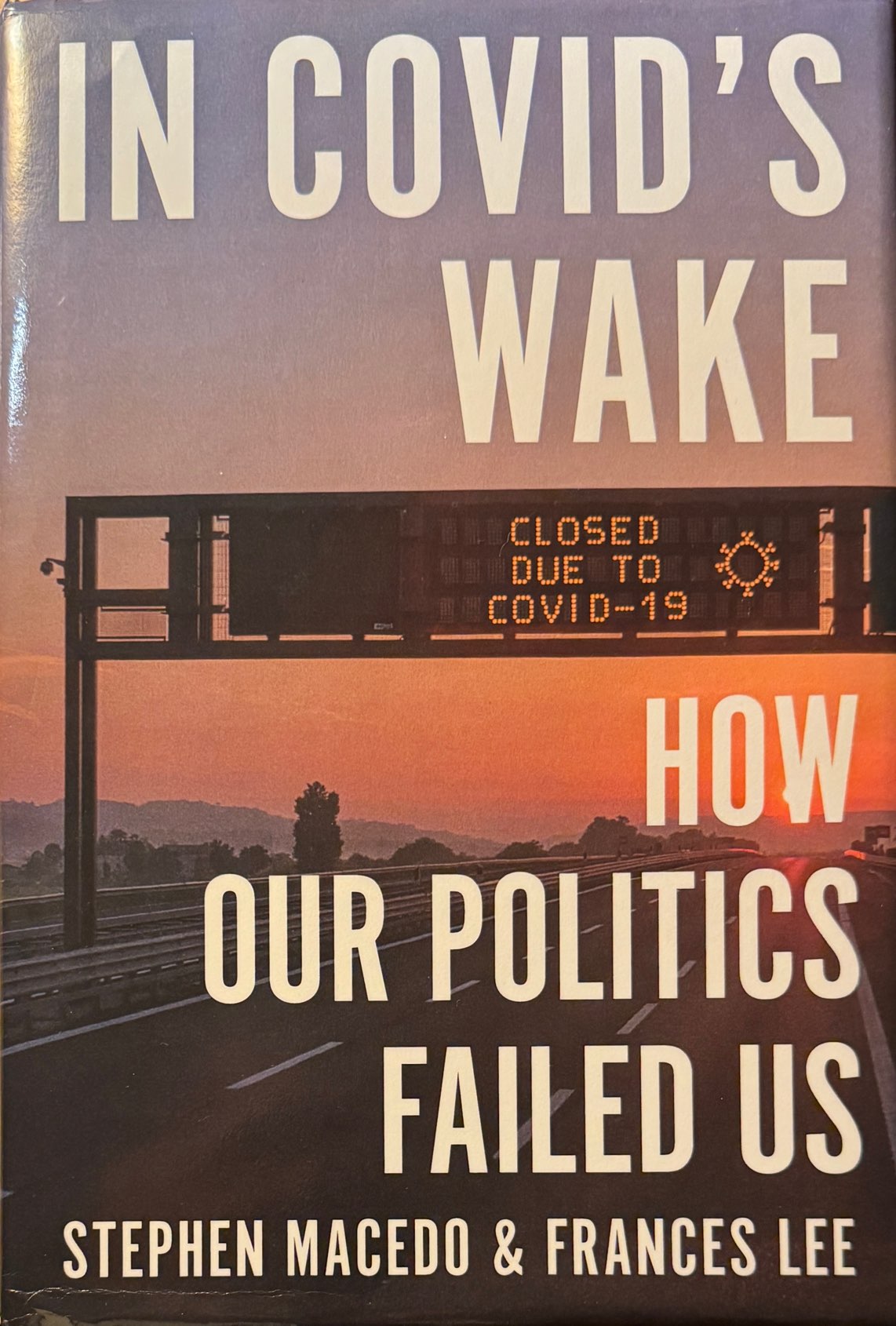

By Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee

I picked this book up after reading a review in The Economist. It has been a fascinating read for me. If nothing else, it has shattered many of my assumptions and beliefs about COVID, including the origin and containment measures.

At the core, the two political analysts discuss how healthcare experts assumed a significant role in public policymaking during the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in the adoption of social measures that were highly focused on saving every single life – often with data that was known to be incorrect – instead of considering the larger harm it would cause to the population, both in the short term and in the long term.

It also highlights how the media and journalists abandoned their duty to question decisions and instead joined in vilifying anyone who held an opposing viewpoint. They reserve their harshest comments for scientists and health experts, who often resorted to name-calling any other scientist or health expert who might have cast doubts. Which, the authors point out, goes against the basic definition of science.

The authors first point out that, before COVID-19 actually hit, how to deal with a viral pandemic was well studied and documented as late as 2019 by multiple agencies worldwide. Without fail, each had concluded that measures such as masks, social lockdowns, and the like would not work. It has not, in the past, either. The virus, once it reaches community spread, can only be dealt with by achieving herd immunity. Like it or not, it will be exposed to everyone. Till a vaccination could be quickly made, such measures of masking and isolation were to target those who were most likely to be fatally affected. This included the old and folks with certain medical histories. This would allow prioritization of valuable medical resources and “flatten the curve”.

For the first few days, that was indeed the response. The authors then detail how China’s touting of the success of shutting down the Wuhan district and then the WHO writing glowingly about it (which the authors contend did not take into account open and truthful data), and then Italy – the first Western country – shutting the country down, everybody threw their manuals away and followed suit.

This, the authors say, was because of a mistaken goal of trying to save every single life at an enormous price to the community. That price is not only about taking personal freedoms away but also about the vast economic and mental health costs that the world will reel thru for decades. The authors believe that health officials aiming for “no lives lost” is a commendable goal. But they are not the ones to make public policy. That has to be done by elected officials with input from many experts, including those outside of health, as well as experts with opposing views. After all, the people elect officials, not elites, to tell them the rules.

The authors outline the significant costs that society is currently bearing. They are fairly scathing about the “elites” (”laptop workers”) who turned a blind eye to the “essential workers” who still had to go to work, and a vast majority of lower-income people who lost their livelihood, temporarily supported by government dole out, and continue to struggle today. They talk about how people died alone and not surrounded by their loved ones, how families could not be around the final rites of their loved ones, and how the mental health of a whole generation of kids has been permanently damaged.

The authors take readers through a wealth of interesting history – how the lab theory of origin was actively shut down by certain powers in the health field, despite severe doubts from others. They discuss how it was widely known that masks were of virtually no use against this particular virus – certainly not in the way most citizens were using them. They further take us through how there was overwhelming data about the effectiveness of the first vaccination, but none of the booster doses have been proven to be of that level of fidelity.

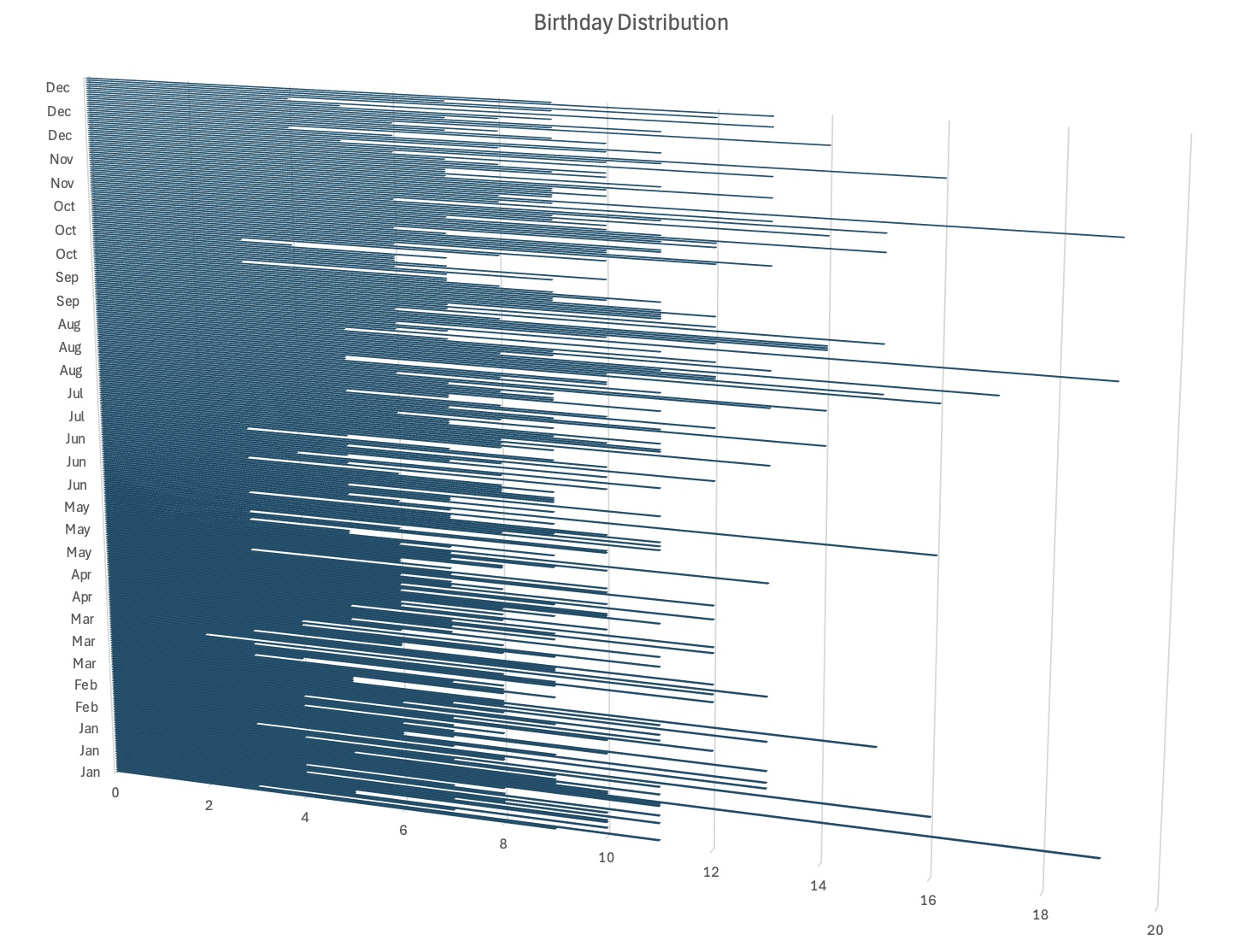

The authors painstakingly take us through the data of red states versus blue states. And how the political leaning of folks led to the timing of the measures. Red states, almost without fail, opened up faster but were far slower in vaccinations. Governors of red and blue states differed markedly in their responses, resulting in significantly different outcomes in terms of COVID-19 cases and deaths. And yet, virtually all of them returned to power with significant margins.

Remember Sweden? They were vilified for not taking what was then considered the appropriate steps. The topic was hotly contested there, too. However, they adhered to the original game plan. As a result, while they initially took a larger hit than most other countries, in the end, all their statistics (until vaccinations were available) turned out to be the same as those of others. Just like the original handbook on pandemic has predicted!! And they today have far fewer cases of economic displacement or mental health issues compared to the beginning of the pandemic.

Ultimately, the authors are careful to point out that mistakes are often made during the heat of the moment. And not everybody has the same way of looking at an event. However, now that we are much separated from the pandemic, there needs to be a national debate. If not, they are afraid that we will commit the same mistakes of leaving public policy to elite experts in a field, and worse, shut down each other without listening to the other side of the debate. Worse, all in the name of “science”!

A must-read, in my opinion.